Tagebuch Dienstag, 5. Oktober 2021 – Kistenküche

Am Montag abend war ich gerade im Bad, um mich für ein frühes Zubettgehen fertigzumachen, als ich seltsame Piepstöne hörte. Zuerst dachte ich, mein Staubsaugerroboter würde mich wieder auf irgendwas aufmerksam machen wollen – voller Auffangbehälter, leerer Akku, der generell elendige Zustand der Klimapolitik –, aber das Geräusch kam nicht aus dem Arbeitszimmer, wo er nach einem kurzen Aufenthalt in der Küche wieder steht. Erst beim Blinken aus der Bibliothek wurde mir klar: DAS FESTNETZTELEFON KLINGELT! Ich war allerdings nicht schnell genug, aber es war natürlich das Mütterchen, das schließlich als einzige meine Nummer besitzt. Dachte ich. Denn gestern morgen klingelte es wieder, und es war meine Mailbox, die mir die Nachricht des Mütterchens von vorgestern abend abspielte. Ich kann also von einem Menschen und einem Dings angerufen werden.

Ich musste gestern erst einmal ergoogeln, wie ich einstellen kann, dass die Box sich nicht schon nach dreimaligem Läuten einschaltet. Oder wie sie mir mit einem Signal anzeigt, dass jemand auf sie gesprochen hat. Oder wie ich sie abstelle, weil sie mir nicht anzeigt, dass jemand auf sie gesprochen hat und mich stattdessen anruft, was ich gar nicht will. Ich hatte vergessen, wie kompliziert Telefone sind.

—

Mittags einen Spaziergang gemacht, weil ich mich bewegen muss bei acht Stunden Agenturschreibtisch. Wenn ich so lange in Bibliotheken sitze, renne ich öfter durch die Gegend, um Buch 1 bis 35 in 20 Etappen an den Platz zu holen. Im Home Office hole ich höchstens mal Tee, das reicht nicht, um Rückenschmerzen vorzubeugen. Also gehe ich spazieren. (Meist zu Packstationen.)

AuĂźerdem beim Metzger eine Zutat bestellt, die ich noch nie bestellt habe, noch nie bestellen wollte und auch noch nie essen wollte, aber das Rezept will das, also mache ich das. Freitag wird das Zeug abgeholt und muss sich sehr anstrengen, mich von sich zu ĂĽberzeugen.

Das Buch High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America ist übrigens daran schuld, dass ich komische Dinge bestelle. Ich habe es erst zu zwei Dritteln durch, empfehle es aber schon dringend weiter. Die gleichnamige Netflix-Serie ist ein müder Schatten gegen die Faktendichte und den sehr gut lesbaren Stil des Buchs. Am Ende dieses Eintrags steht ein kurzer Ausschnitt aus der Einleitung, und bisher löst das Buch eben diese ein.

Ansonsten gab es einen Auflauf aus Resten der vorgestern genutzten Chorizo und Brokkoli (aus der Biokiste) neben dem mittäglichen Müsli, in das ich letzte Woche Honigmelone geschnipselt hatte (aus der Biokiste) und diese Woche Weintrauben (aus der Biokiste). Zum Auflauf gab es grünen Salat (aus der Biokiste) und Radicchio (aus der Biokiste) sowie Chinakohl, der auch noch von vorgestern übrig war. Einiges aus der Kiste hätte ich auch so im Haus gehabt, aber momentan freue ich mich immer wie das Klischee einer sparsamen Hausfrau aus den 1950er-Jahren, wenn ich die Biokiste leerkriege. Und ich esse Dinge, die ich sonst nicht esse wie Chorizo-Aufläufe. Und, ja, mehr Salat als sonst, schon gut.

—

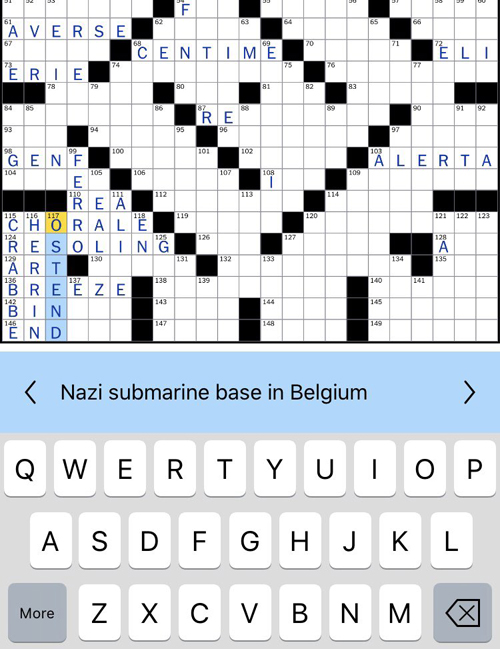

Das Bild hatte ich Samstag schon vertwittert mit der Bemerkung: „Was versuche ich mich auch an Crosswords von 1942?“ Das Rätsel war für mich unlösbar ohne Autocheck – damit zeigt die App der NY Times gleich an, ob die Eingabe korrekt ist, weswegen die Buchstaben blau sind und nicht schwarz. Neben Clues, mit denen ich wirklich nicht gerechnet hatte – Nazi-Basen in Belgien? What the hell? – und vielen Generälen oder Flugzeugnamen, die zur Zeit des Zweiten Weltkriegs vermutlich mehr Menschen geläufig waren als uns heute, hatte ich vor allem Schwierigkeiten mit den Umschreibungen, die mir – logischerweise – sehr altmodisch vorkamen. Ich löse doch lieber Rätsel von heute, in denen ich Songtexte wiedererkenne oder TV-Charaktere oder lustige Memes.

An den Tweet hängte ich noch einen weiteren Screenshot aus der App, in dem der Chefkorrektor des NYT-Kreuzworträtsels ein bisschen zur Geschichte des Zeitvertreibs plaudert.

—

„While millions of Africans were brought in chains to the New World, the botanical connection to the African continent remained relatively small. The list is even smaller in the United States, where the weather did not permit the introduction of such tropical species as ackee, the oil palm, kola, true African yams [was in vielen Thanksgiving-Rezepten als „yams“ bezeichnet wird, sind Süßkartoffeln], and other tubers. The few plants that could survive – okra, watermelon, and black-eyed peas – have, however, remained emblematic of Africans and their descendants in the United States and of the region in which most of them toiled, the American South.

Okra is perhaps the best known and least understood outside African American and Southern households. Prized on the African continent as a thickener, it is the basis of many a soupy stew and is served up in sheets of the slippery mucilage that it exudes. Okra probably was first introduced into the continental United States in the early 1700s, most likely from the Caribbean, where it has a long history. Colonial Americans ate it, and by 1748 the pod was used in Philadelphia, where it is still an ingredient in some variants of the Philadelphia gumbo known as pepperpot. In 1781 Thomas Jefferson commented on it as growing in Virginia, and we know that it was certainly grown in the slave gardens of Monticello. By 1806 the plant was in relatively widespread use, and botanists spoke of several different varieties.

Our American word okra comes from the Igbo language of Nigeria, where the plant is referred to as okuru. It is the French word for okra, gombo, that resonates with the emblematic dishes of southern Louisiana known as gumbo. Although creolized and mutated, the word gumbo harks back to the Bantu languages, in which the pod is known as ochingombo or guingombo. The word clearly has an African antecedent, as do the soupy stews that it describes, which are frequently made with okra.

Watermelon has been so connected with African Americans that it is not surprising to learn that the fruit is believed to have originated on the African continent. Pictures of watermelons appear in Egyptian tomb paintings, and in southern Africa they have been used for centuries by the Khoi and San of the Kalahari. More than 90 percent water, the fruit is useful in areas where water may be unsafe, and it is also especially prized to cool folks down in hot weather.

Watermelons arrived in the continental United States fairly early on in the seventeenth century and were taken to heart and stomach rapidly as new cultivars were developed that were more suitable to the cooler weather. As with okra, watermelon has been indelibly connected to African Americans. Indeed some of the most virulent racist images of African Americans produced in the post-Civil War era involve African Americans and the fruit. […] National attitudes toward watermelon have changed, but the fruit and its stereotyped history still remain a hot-button issue for many.

[The black-eyed pea] was perhaps best known as an ingredient in the South Carolina perloo (or composed rice dish or pilaf) known as Hoppin’ John. Legumes are the among the world’s oldest crops. They have been found in Egyptian tombs and turn up in passages in the Bible. The black-eyed pea, which is actually more of a bean than a pea, was introduced into the West Indies from Central Africa in the early 1700s and journeyed from there into the Carolinas. The pea with the small black dot is considered especially lucky by many cultures in West Africa. While the pea was certainly not lucky those who were caught and sold into slavery, the memory of the luck it was supposed to bring in West Africa lingered on among the enslaved in the southern United States and the Hoppin’ John that is still consumed on New Year’s Day by black and white Southeners alike is reputed to bring good fortune to all who eat it.“

As came okra, watermelons, and black-eyed peas, so came sesame and sorghum. […] Peanuts are New World in origin, yet they remain connected in many minds with the African continent, because it is likely that they moved in general usage in the United States via the Transatlantic Slave Trade. […]

Whether in the slip of an okra in a southern Louisiana gumbo, the cooling sweetness of a slice of watermelon on a summer day, or the luck of a New Year’s black-eyed pea, the African continent is the origin of many of African American foodways. From its ingredients to its techniques and its hospitality, rituals, and ceremmonies, the continent has remained a vivid memory: one that left its mark on its displaced children in the New World.“

Jessica B. Harris: High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America, New York/London 2012, S. 16–19.