Links am Freitag, 26. Februar 2021

Im Deutschlandfunk hörte ich gestern die wöchentliche Sendung „Historische Aufnahmen“. Darin wurde der Dirigient William Steinberg (1899–1978) vorgestellt. Das Stück, dessen vierten Satz ich noch komplett hören konnte, war Gustav Holsts Orchestersuite „Die Planeten“. Laut DLF ist die Einspielung des Boston Symphony Orchestras unter Steinberg von 1970 bis heute eine, an der sich andere messen lassen müssen. Wie praktisch, dass sie auf YouTube steht.

Erst gestern gemerkt, dass sich Manfred Mann für „Joybringer“ an dieser Suite bedient hat. Daher musste ich sofort an Rachmaninoff denken, aus dessen Klavierkonzert Nr. 2 sich Eric Carmen für „All by myself“ eine Melodie borgte.

—

Wendy Lower hat ein Buch über ein fürchterliches Foto geschrieben:

To Catch a Killer: Uncovering the Massacre of a Jewish Family in Nazi Europe

Ich habe das Bild beim ersten Auftauchen im Artikel nur kurz angeschaut und dann schnell weitergescrollt, auch wenn ich immer ein schlechtes Gewissen dabei habe, mich Abbildungen der NS-Morde nicht aussetzen zu wollen. Lower geht auch auf den Umgang mit diesen Bildern ein.

„Although the documentary and photographic record of the Holocaust is greater than that of any other genocide, incriminating photographs like this that catch the killers in the act are rare. In fact, there are so few that I can list them here: an SS officer aiming his rifle at a Jewish family fleeing in the fields of Ivanograd, Ukraine; naked Jewish men and boys being forced to lie facedown in a pit (the “sardine method”) as they are being shot in Ponary, Lithuania; Jewish women and children, at the moment of death, falling into the sand dunes of Liepāja, Latvia; an execution squad firing in Tiraspol, Moldova; naked Jewish women and girls being finished off by Ukrainian militia in Mizoch; one photograph from Ukraine with the caption “last living seconds of Jews in Dubno,” showing men being shot execution-style against a brick wall; another, also from Ukraine, captioned “the last Jew in Vinnytsia,” showing a man kneeling before a pit with a pistol to the back of his head; Jews in Kovno (Kaunas) being bludgeoned to death by Lithuanian pogromists; and a few more without captions, apparently taken in the Baltic states or Belarus and depicting the Holocaust by bullets.

Most of these images have been blown up and displayed in museum exhibitions; many are retrievable on the internet. They are few but represent the murder of millions. These iconic snapshots of the Holocaust give the false impression that such images are numerous, yet they number not many more than a dozen, and we know little, if anything, about who is in them, and even less about who took them. […]

Mass murder requires a division of labor among a multitude of perpetrators, and in the Holocaust that combined effort cut across ethno-cultural lines. I was to learn that the photographer was a Slovakian security guard, mobilized for the invasion and occupation of the Soviet Union in 1941 and stationed in Nazi-occupied Ukraine. Like millions of other soldiers, he got swept up in the camera craze of the 1920s and 30s, and when he was drafted, he packed his new Zeiss Ikon Contax to document historic events and foreign terrain. […]

The photographic documentation of the Holocaust is especially rich because the events coincided with the mass production and consumption of the small handheld camera. During the war, Hitler‚Äôs propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, embedded 15,000 photojournalists in all theaters of the conflict, producing more than 3.5 million images. The pocket snapshot was a common item in the soldier‚Äôs knapsack. And as German soldiers seized and occupied territories formerly held by the Soviet Union in 1941 and 1942, they photographed what they encountered. World War II was not only the most destructive armed conflict ever; it was also the most photographed. […]

Photographs, if we choose to study them, open up questions and lead us down paths of discovery. There are details in the Miropol photograph that we were not supposed to witness. Some postwar theorists of photography would urge us not to look at, let alone scrutinize, the suffering of others. In 1988, when scholars and museologists deliberated over the visual content of the United States Holocaust Memorial’s Museum’s exhibits, they explored the “question of explicit imagery including the ‘pornography of murder, nudity and violence in a museum.’”

The museum’s creators were clear that to avoid all graphic visuals—images that elicit shock and outrage—would be to forsake the truth of Nazi evil. They did not want to display victims in a way that would further humiliate them or embarrass their families and descendants, or encourage voyeurism. They feared that images of sexual violence and nude corpses might excite erotic fantasies. Depictions of death “precisely because its meaning eludes us and because it is universal and ineluctable titillate, fascinate, and compel attention.” Viewers should not “lose sight of the fact that each of the corpses in a pile was a single, complex, multi-faceted human being with parents, families, loved ones, personal dreams and expectations and thwarted aspirations.”

The cultural critic Susan Sontag argued that the shock of atrocity photography “wears off with repeated viewings.” I disagree. The risk of desensitization to such images exists when we have no knowledge of their history and content. The more I learned, the more the Miropol image came to life.“

(via @c_emcke)

—

Als Rausschmeißer ein Artikel, der möglicherweise hinter der Paywall ist, den ich aber gestern dringend lesen musste:

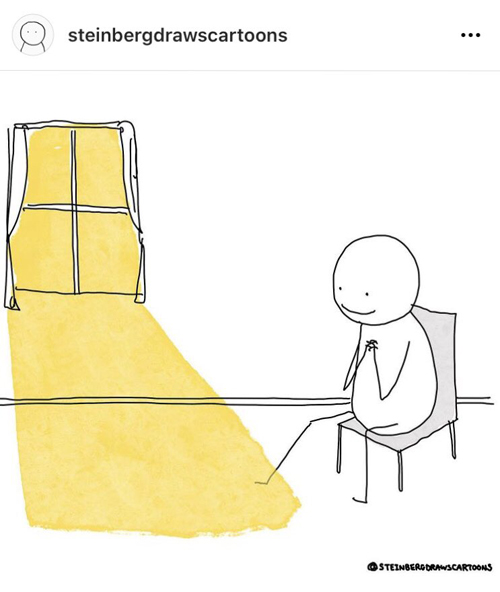

The joy of vax: The people giving the shots are seeing hope, and it’s contagious

„The happiest place in medicine right now is a basketball arena in New Mexico. Or maybe it’s the parking lot of a baseball stadium in Los Angeles, or a Six Flags in Maryland, or a shopping mall in South Dakota. The happiest place in medicine is anywhere there is vaccine, and the happiest people in medicine are the ones plunging it into the arms of strangers.

“It’s a joy to all of us,” says Akosua “Nana” Poku, a Kaiser Permanente nurse vaccinating people in Northern Virginia. “I don’t think I’ve ever had an experience in my career that has felt so promising and so fulfilling,” says Christina O’Connell, a clinic director at the University of New Mexico. “There’s so many tears” — of joy, not sadness — “that it’s almost normal at this point,” says Justin Ellis, CVS pharmacist in Laveen, Ariz.

For health-care workers, the opportunity to administer the vaccine has become its own reward: Giving hope to others has given them hope, too. In some clinics, so many nurses have volunteered for vaccine duty that they can’t accommodate them all.

Many of those same health-care workers spent last year sticking swabs up the noses of people who thought they might have the coronavirus. The work was risky. The patients were scared. There was never relief, just limbo. The arrival of The Shot has transformed the grim pop-up clinics of the pandemic into gratitude factories — reassembly lines where Americans could begin to put back together their busted psyches.

“I will never forget the face of the first person I vaccinated,” says Ebram Botros, a CVS pharmacy manager in Whitehall, Ohio. It was an 80-year-old man who said that he hadn’t seen his children or grandchildren since March.

Botros’s pharmacy is in a diverse community outside Columbus. As an African American who immigrated to the United States from Egypt, Botros feels a special responsibility to reassure Black patients who may be ­vaccine-averse from a historical legacy of medical abuse. One 89-year-old Black woman told Botros she had never gotten a shot before in her life. “I explained to her: ‘This is very important. It’s painless, and it’s going to help you have your life back to normal,’ ” he says. Her grandson later reached out to Botros to thank him personally — and told him that the woman called all of her friends and urged them to get their shots, too.“

—

Die erste Person aus meiner Twitter-Timeline ist geimpft!

—